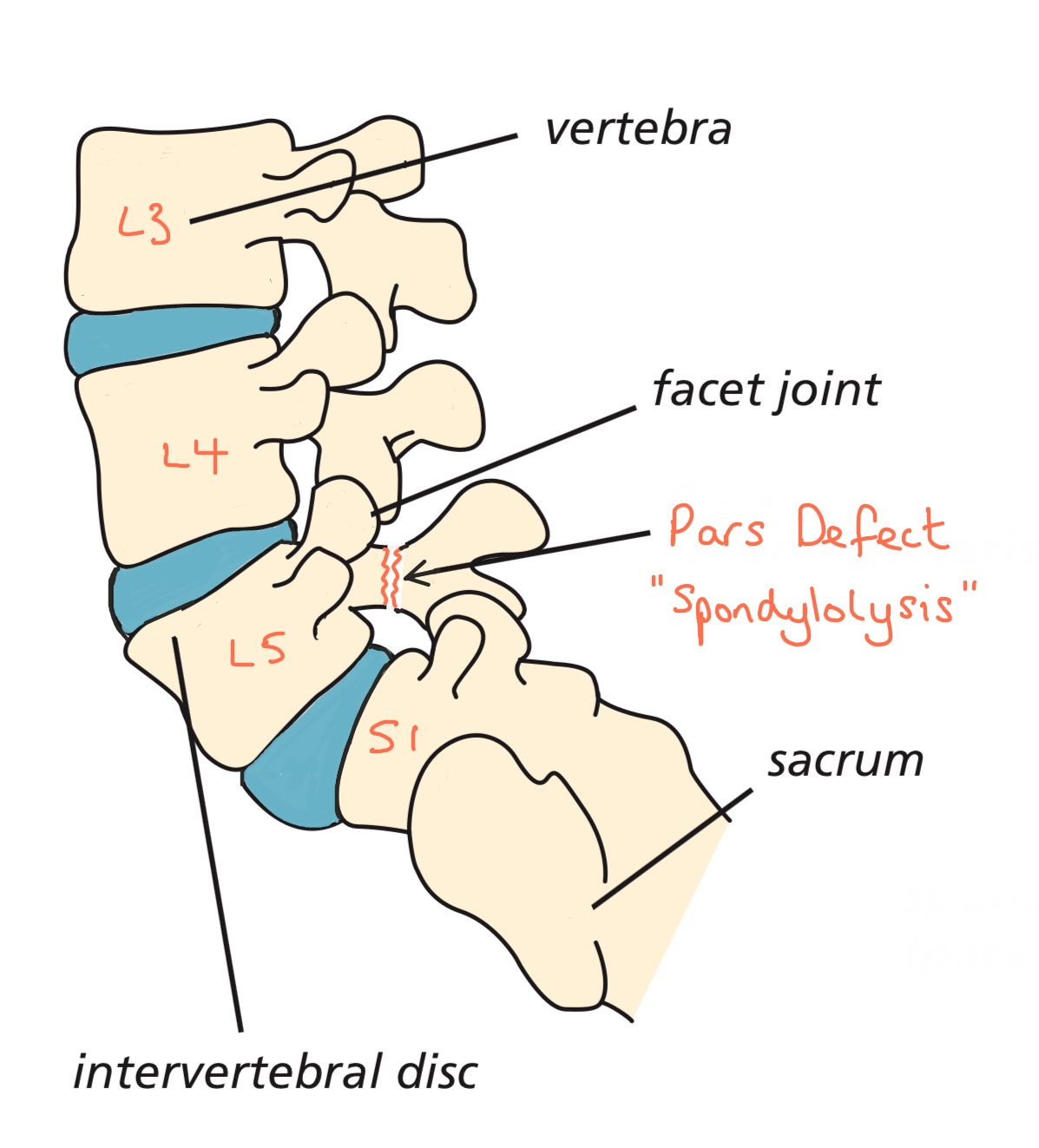

The ‘pars interarticularis’, is a small length of bone that joins the facet joints of one vertebra to the facet joints of the vertebra below it. There is a pars interarticularis on each side of the vertebrae at the back of the spine.

A pars defect is a small break or fracture in the bone that connects the facet joints and they can become separated and this is also called “Spondylolysis”.

Pars defects are most common in children and adolescents before the bones are fully matured and in high achieving athletes. See section on Pars Defects.

In 80% of cases pars defects occur on both sides of the vertebra (bilateral) but they can can happen on only one side (unilateral). More than 85% of pars defects are found in the L5 vertebra and about 10% are in the L4. Rarely they are found in the L3 and L2 vertebrae.

If the stress fracture weakens the bone so much that it is unable to maintain its correct position and the vertebra can start to slips out of place. This is called a “Spondylytic Spondylolisthesis” and refers to the slipping of one vertebra over another. The two vertebrae can become unstable and cause both back pain and also leg pain.

Most people who have a pars defect do not even know they have one and they experience minimal or no symptoms. For those people who do experience symptoms (See section of Pars Defects for more details), conservative management usually improves the symptoms without treatment. However for some people, more interventional treatment is required.

Initial treatment involves a pars injection which is performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. This will hopefully gives long term pain relief, however if the pain relief is only short-lived this is diagnostically very important; to consider surgically repairing the pars defect we have to be sure that this is the source of the pain.

The type of operation performed to repair a pars defect depends on whether there is a spondylolisthesis or not, therefore the operations for a spondylolysis and a spondylytic spondylolisthesis are addressed separately.

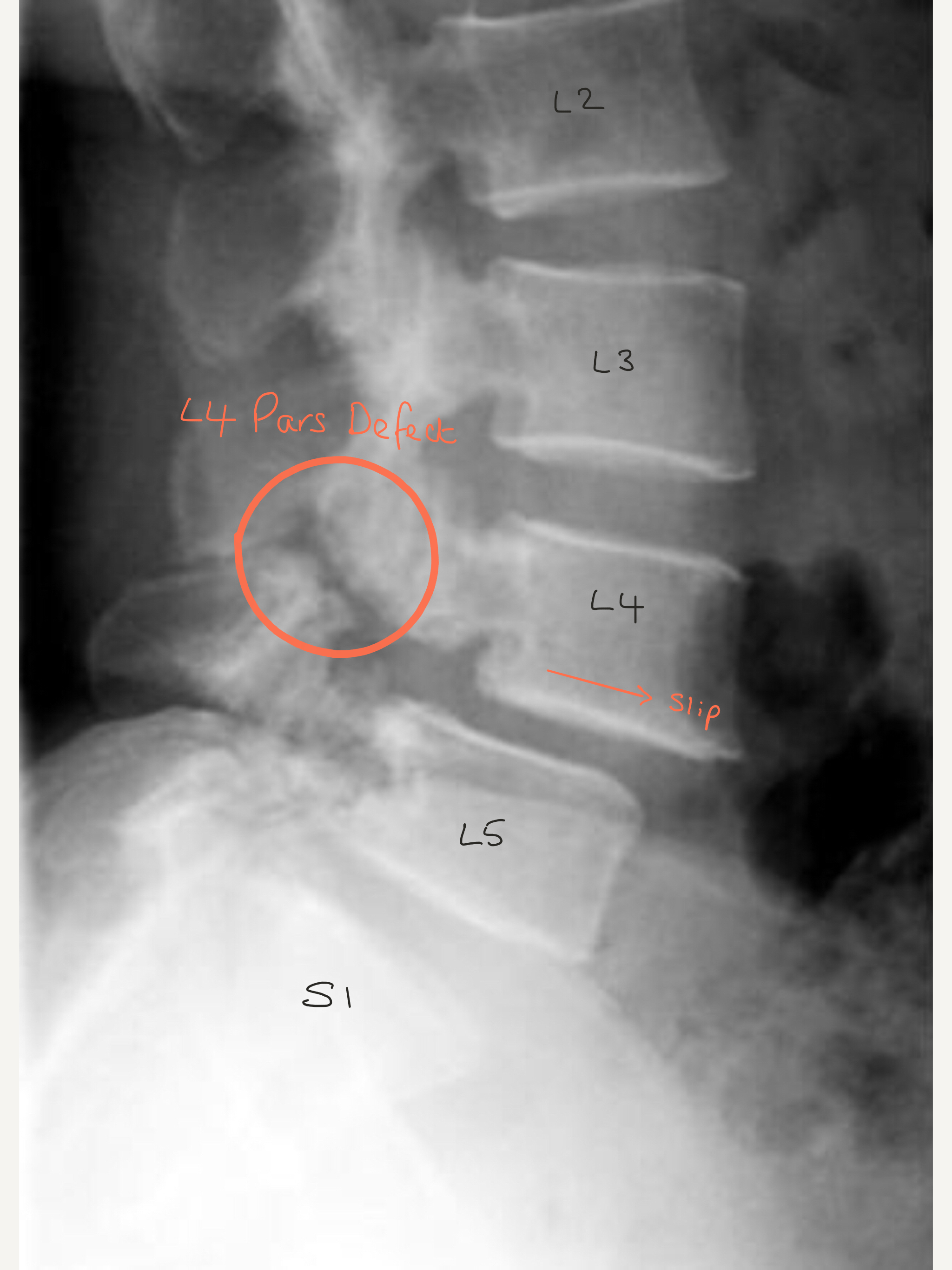

The diagram shows a pars defect

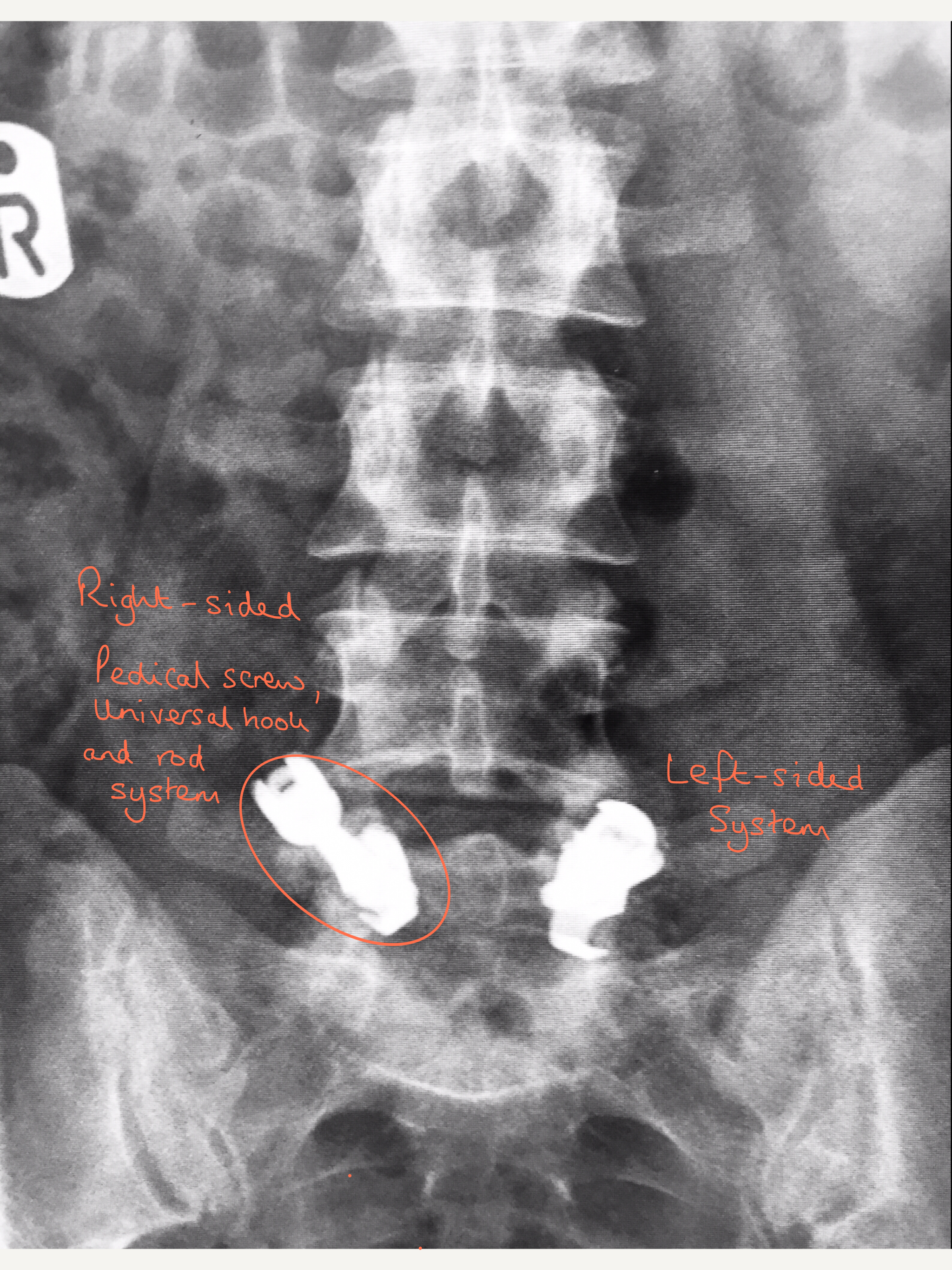

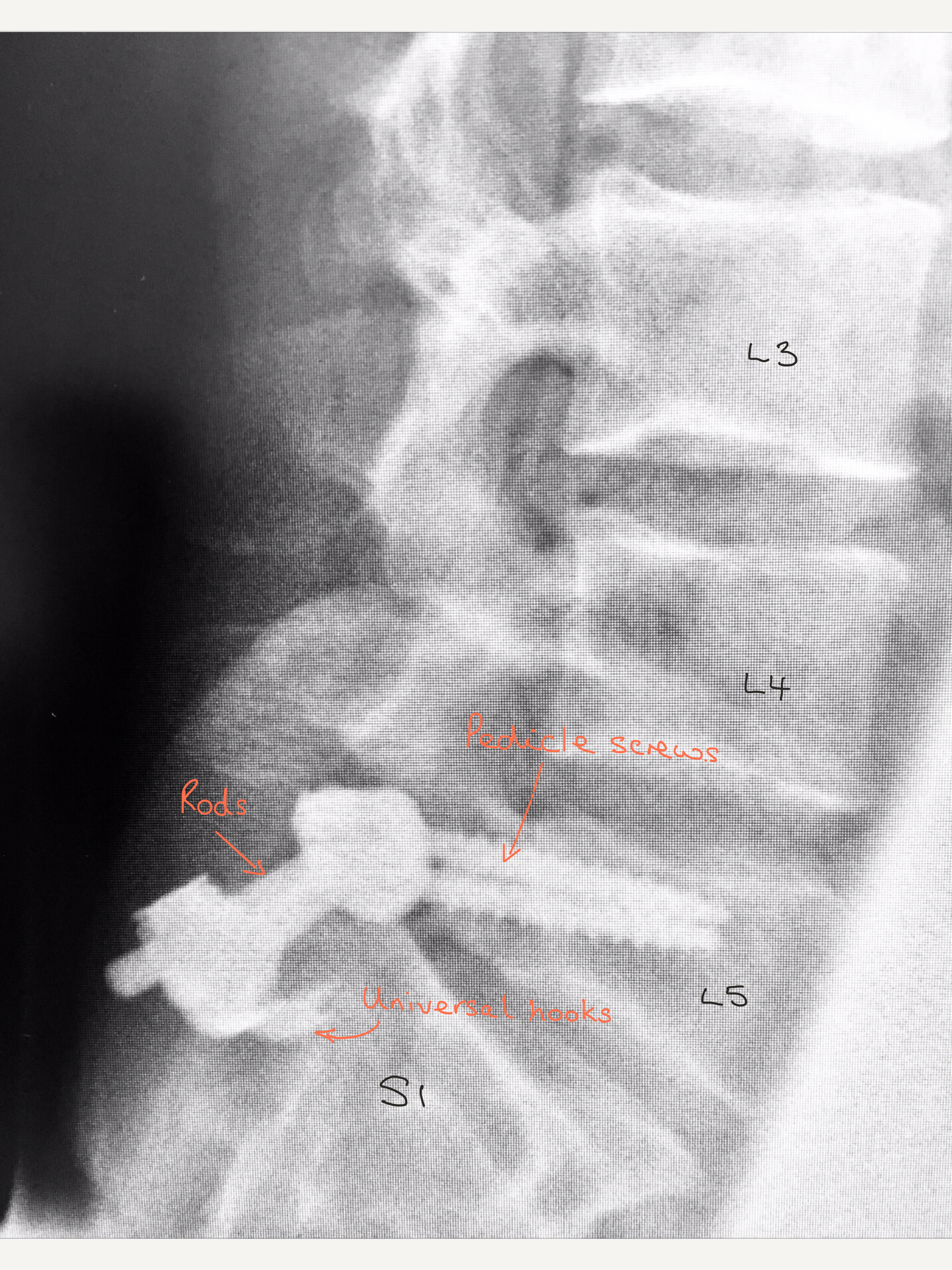

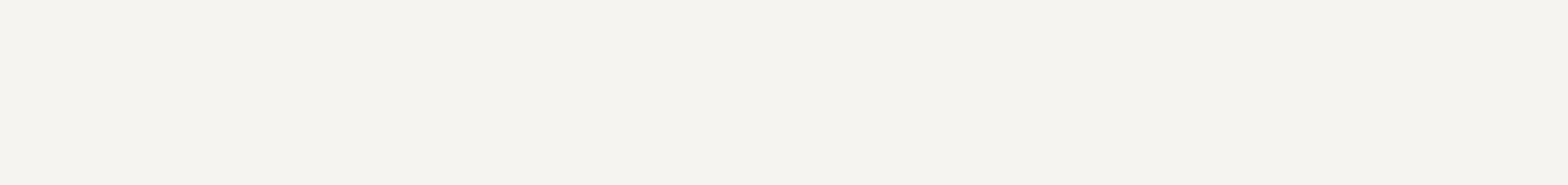

X-ray showing front view of the system of pedical screws, hooks and rods used in a pars repair at L5

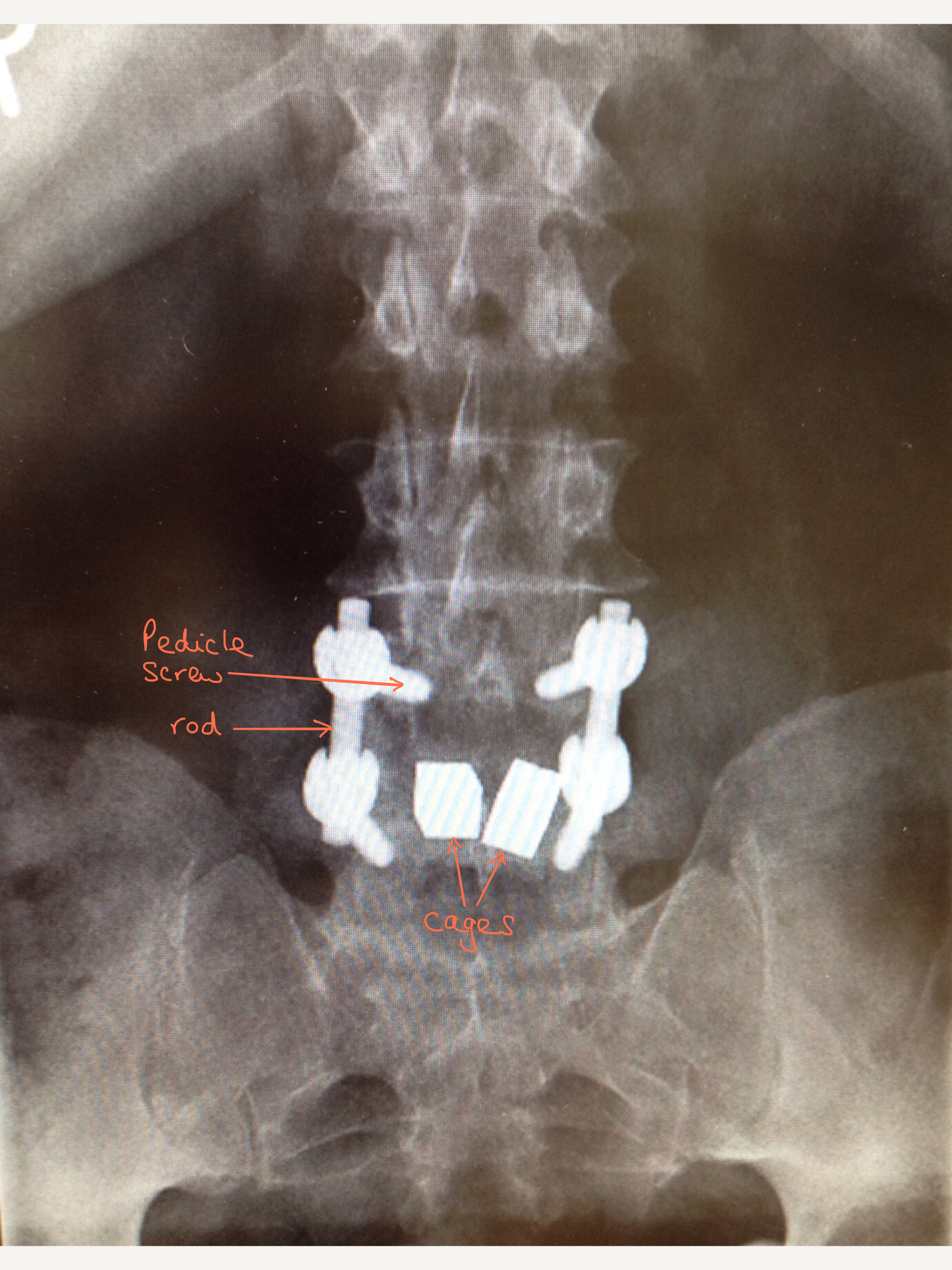

This X-ray shows a lateral (side) view which gives a clearer picture of the different parts of the system.

1) Instrumented Fusion of Spondylolysis

There are several techniques used to repair a Spondylolysis caused by pars defects and Mr Hilton prefers to use pedicle screws and rods with a universal hook system. This system holds the vertebra together and prevents movement at the segment that is being fused, like an internal scaffolding system.

The top screw or screws are placed into part of the vertebra called the pedicle, which go directly from the back of the spine to the front, on both sides, above the unstable spinal segment. The universal hook is placed into the vertebra below the unstable spinal segment and a rod is placed between the pedical screw and hook. This system can be seen on the X-rays to the left.

Bone graft is placed in the non-union fracture site. The bone graft will grow and fuse to the spine esssentially glueing the fracture back together. Once the fusion is established the metalwork is actually no longer needed for stability but most surgeons do not recommend removing it except in rare cases.

2) Instrumented Fusion of a Spondylytic Spondylolisthesis

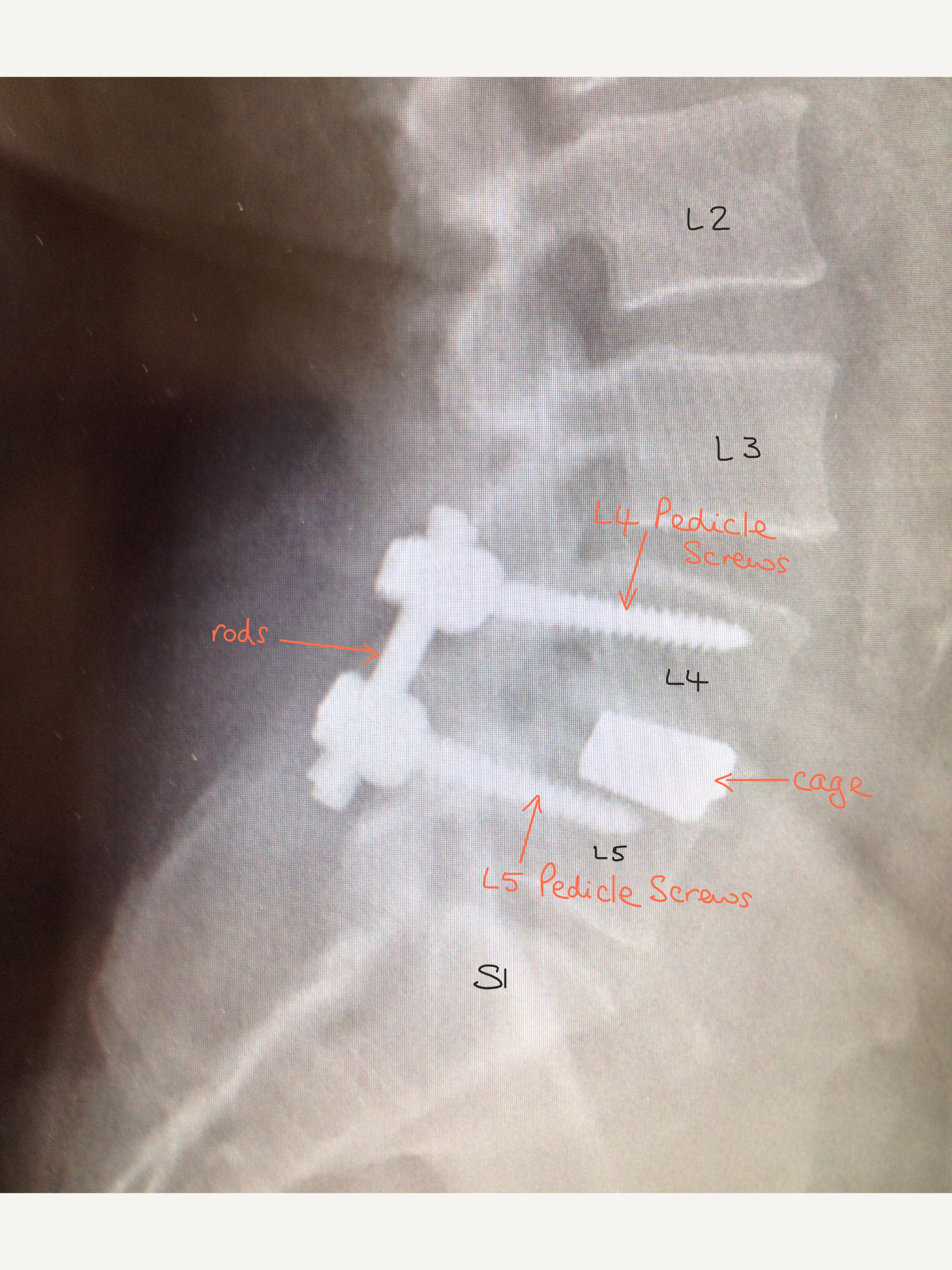

In patients were the pars defect has resulted in a slippage of the vertebrae (spondylolisthesis), their symptoms may also include leg pain/sciatica caused by irritation of the nerves roots at the level of the spondylolisthesis. Therefore surgery needs to address both the problem with the nerves in addition to the instability of the spine. For this type of pars repair Mr Hilton would usually choose an system involving pedicle screws, rods, a cage and bone graft and this is called a Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (PLIF). Before deciding on the exact type of operation and system he will use, several factors are taken into consideration including how narrow the nerve canal has become and how much the vertebra has slipped.

The first part of the operation involves a decompression; the intervertebral disc and any tissues irritating the nerves are removed. The interbody cage is then fitted into part of the space created between the two vertebrae and the rest of the space is packed with bone graft. The bone graft is usually the bone that is initially removed from the vertebrae at the beginning of the operation and therefore it is the patients own bone. Although, if there is not enough of the patients bone, some synthetic bone substitute may also be used.

The ‘cage’ (or ‘implant’ as it is sometimes called) is either made of titanium or trabecular metal and although it looks like a solid block on the X-rays, it is actually porous to allow bone to grow into it and becomes incorporated into the fusion. Cages come in different sizes to fit the space between your vertebrae perfectly and either one or two cages can be implanted.

After the decompression and positioning of the cage, the pedicle screws are placed into the pedicle of the vertebra on both sides, above and below the unstable spinal segment. These screws act as firm anchor points to which rods can be connected. The screws and rods act as an internal scaffolding that provides a solid structure to allow a solid bone fusion to take place. Once the bone fusion is complete the scaffolding is actually no longer required but most surgeons do not recommend it is removed unless it actually needs to be which is rare.

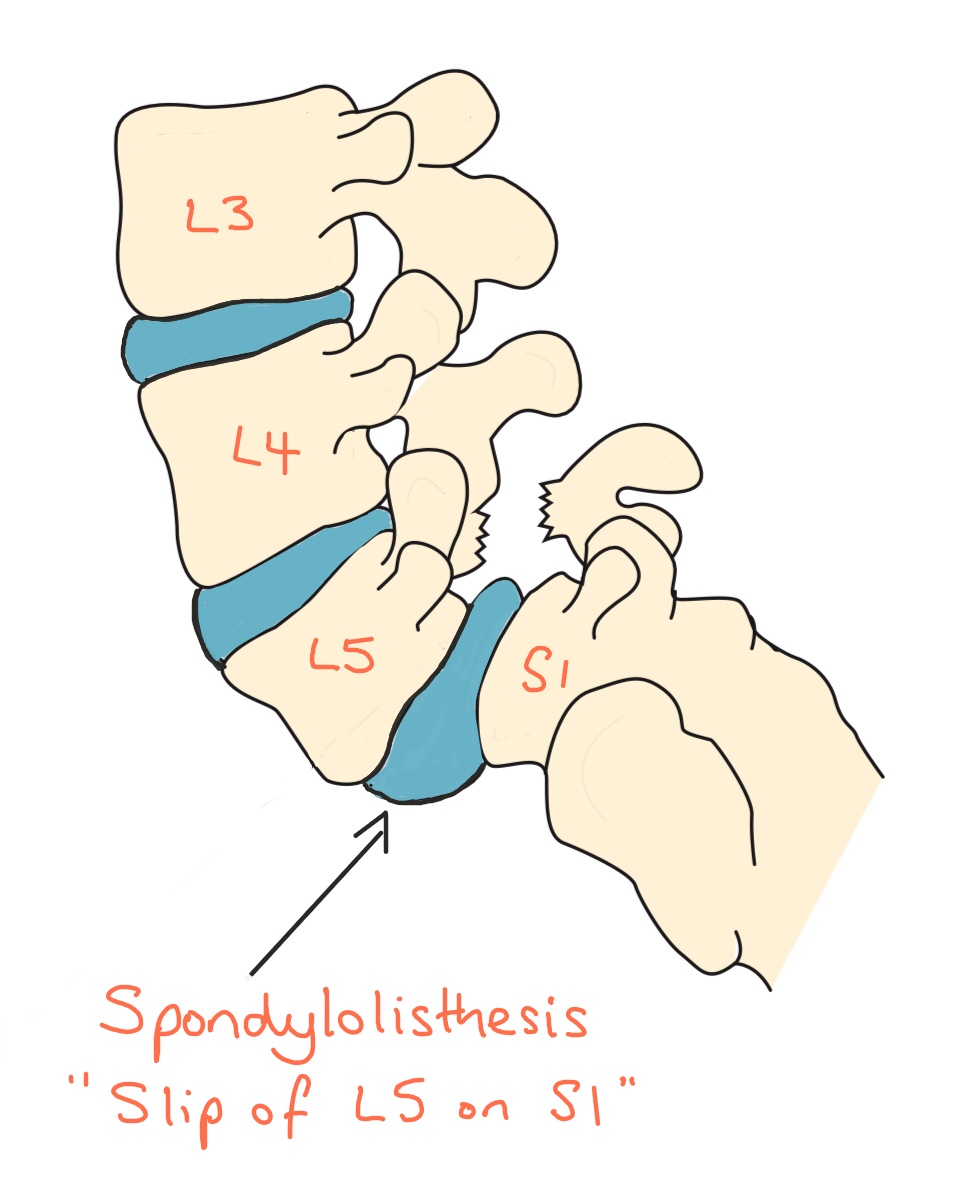

Diagram shows a Spondylolisthesis at L5/S1 caused by a Spondylolytic L5 pars defect

Lateral (side) view X-ray showing the position of the metalwork.

X-ray shows a slip at L4/5 caused by a L4 spondylolysis which is circled.

Front view X-ray – in this case there a two cages.

Risks And Complications Of Instrumented Spinal Fusion

- Bleeding (minor and major vascular damage which can be life-threatening)

- Bruising and swelling around the surgical site

- Infection

- DVT/Pulmonary embolism

- Wound dehiscence

- Minor and major nerve damage (including foot drop, cauda equina syndrome, paralysis) which can be temporary or permanent

- Damage to surrounding soft tissues including muscle

- Failure of bone fusion

- Perineural fibrosis (scarring around nerves causing recurrence of pain)

- Failure to relieve symptoms or recurrence of symptoms

- Failure of implants and misplacement of implants (which can cause nerve damage)

- Back pain

- Medical complications including CVA (Stroke), MI (heart attack), blindness and death

Mr Hilton will take time to thoroughly go through all the risks and complications of a instrumented repair of a pars defect before you decide whether to proceed with the surgery. The risks and complications are similar to those of all spinal surgery and therefore for more detailed information about the general risks and complications please look at the ‘Risks and Complications’ section.

Factors Which May Affect Spinal Fusion And Your Recovery

There are a number of factors that can significantly reduce the chances of a solid fusion following surgery and these include:

• smoking

• diabetes or chronic illnesses

• obesity

• malnutrition

• osteoporosis

• post-surgery activities (twisting exercises, lifting heavy weights, not taking medical advice on what activities you should be doing)

• long-term (chronic) steroid use

Of all these factors, smoking has the biggest negative effect on bone fusion (and the risk of post-operative infections). Nicotine is a bone toxin (poison) and can inhibit the ability of the bone-growing cells in the body (osteoblasts) to grow bone and therefore stop the bone fusion. In order to give yourself the best chance of bone fusion, you should stop smoking ideally 2 -3 months before your surgery.

Your surgery may be delayed if you have not stopped smoking (or taking nicotine in another form) beforehand.

There is evidence that NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) including ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, meloxicam and aspirin may slow or even prevent bone fusion.

NSAIDs affect prostaglandin synthesis, and, as prostaglandins are essential for normal bone turnover and new bone formation, the use of NSAIDS may ultimately affect bone healing by inhibiting new bone formation. Animal studies involving NSAIDs have shown a delay in healing time and non-union but no long term studies have been done on humans yet. Although it is a theoretical risk, a lot of spinal surgeons worldwide advise patients not to take NSAIDs following spinal fusions.

If you need to take NSAIDs, for example for rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, please discuss this with Mr Hilton.

Recovery

Following surgery, most patients usually stay in hospital for 1-2 days and this partly depends on their general health. Some pain/tenderness and bruising is normal around the operation site.

Prior to your discharge, you will spend time with the hospital physiotherapist who will help you to mobilise and will advise you on appropriate exercises to do once you return home. It is essential you practice these exercises everyday.

Mr Hilton or one of his team will see you at about 7 – 10 days following your operation to check your wound and also to see how you are getting on. Patients are advised NOT to change their own dressings. You are at risk of getting a wound infection if you change your own dressing.

If you are concerned about your wound or you feel it is necessary to change the dressing before your wound check appointment, then either:

Place a fresh dressing over the top of the original dressing

OR

Contact the hospital or your GP practice.

The nature of spinal surgery is not to ‘cure’ a condition but is aimed to provide benefit with a good percentage improvement and relief of symptoms. Good relief from back pain following surgery usually occurs in approximately 70% of cases (up to seven out of 10 people). Although often there is an immediate change in the ‘nature’ of the pain, the improvement is expected to take several months and is helped by regular rehabilitative exercises.

Physiotherapy

The first part of your treatment is stabilising and fusing the pars defect, the second part of your treatment journey is your rehabilitation which involves exercise. You will be referred to a physiotherapist as an outpatient, however before you see the physiotherapist please continue to do the exercises you were taught in hospital on a daily basis.

The aim of doing exercises is to rehabilitate and improve the strength of the core muscles supporting the spine and pelvis.